Canada has narrowed its next-generation submarine competition to two boats that represent different philosophies of conventional undersea warfare. The German–Norwegian Type 212CD by ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS) is a compact, exceptionally quiet design optimized for prolonged covert presence in northern approaches and other complex littorals. South Korea’s KSS-III Batch II by Hanwha Ocean is a larger, blue-water hull with a built-in vertical launch system and the energy budget to carry more weapons and operate farther from home. Both appear to be capable platforms.

Requirements

The first step is to assess what the Government of Canada wants out of its new submarine fleet and what capabilities it will need to achieve its objectives. I’m starting here because there is a common misconception that Canada needs submarines exclusively for Arctic patrol and surveillance, which is false. While it’s true that Arctic sovereignty and security are quite rightfully a preoccupation for the government, patrolling Canada’s Arctic is not the only capability Canada needs out of its new fleet. However, it is the most common argument in favour of a submarine fleet since Arctic sovereignty remains popular within Liberal and Conservative circles alike, along with mainstream media.

Unfortunately, this narrative forces a lopsided conversation about the role these new boats will be expected to play over the coming decades. In addition to Arctic operations, these subs will be expected to deploy far into the North Atlantic with NATO and push across the Pacific to support the Indo-Pacific Strategy. Ottawa’s own defence policy update ties submarine recapitalization to contributions with allies in both theatres.

This implies a blue-water capability, which means these conventionally powered submarines must be able to deploy and fight in the open ocean, far from home ports and daily logistics, for extended periods. This requires long range and endurance for transoceanic transits, sustained submerged persistence through air independent propulsion (AIP) and high-capacity batteries to minimize snorkelling, and habitability and maintenance margins that keep the crew and systems effective past the 30- to 60-day mark. Simply put, the new boats must be able to cross an ocean, remain covert and lethal on station, and deliver effects.

The government further stipulated specific capabilities that the new submarines must have in one of its press releases stating “Through the Canadian Patrol Submarine Project (CPSP), Canada will acquire a larger, modernized submarine fleet to enable the Royal Canadian Navy to covertly detect and deter maritime threats, control our maritime approaches, project power and striking capability further from our shores, and project a persistent deterrent on all three coasts.”

What caught my attention here is the ability to project power and striking capability further from our shores. Power projection is synonymous with a blue-water capability; however, a striking capability, which I take to mean a land strike capability, is not typical for a conventionally powered SSK, which are typically armed only with torpedoes to take out other submarines or surface vessels.

To sum up, Canada’s new subs must be able to:

- Patrol the Arctic with under-ice capability year-round

- Deploy with NATO in the North Atlantic and support Canada’s commitment to the Indo-Pacific Strategy – A blue-water capability

- Remain submerged for three weeks or more at a time

- Covertly detect and deter maritime threats

- Control Canada’s maritime approaches

- A range of 7000 + nautical miles

- Project power far from home ports

- Anti-surface and subsurface warfare

- Land-attack capability via cruise and/or non-nuclear ballistic missiles

- Insert Tier-1 special operators on coastal infiltration missions

- Conduct intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance in Canadian maritime approaches and abroad.

With that out of the way, let’s look at what each submarine can do.

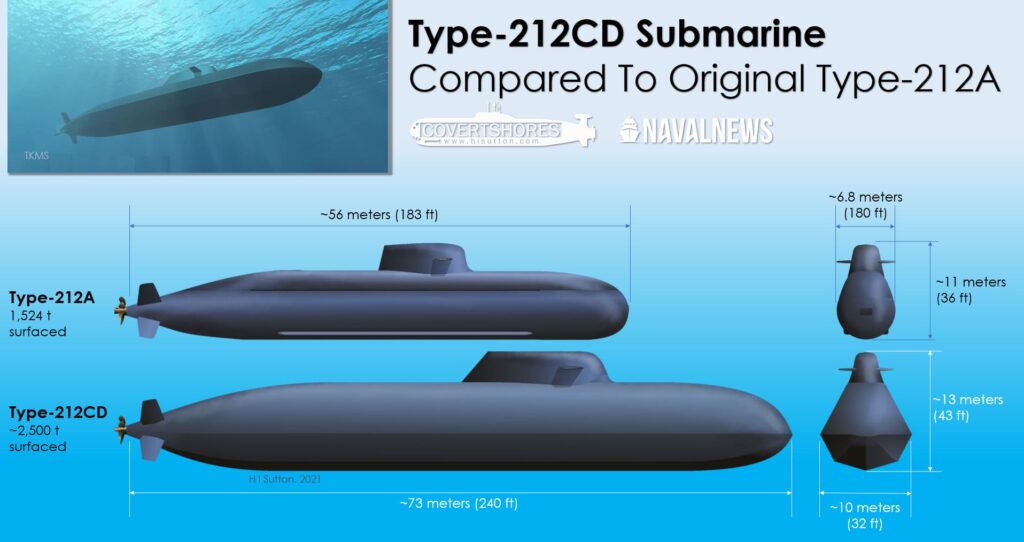

German-Norwegian Type 212CD

The 212CD is the follow-on to Germany’s successful 212A, enlarged for greater payload and endurance and co-developed with Norway under a binational program. The program’s Critical Design Review was completed in August 2024, marking the formal end of detailed design and a gateway to full-rate production. In December 2024, the German government expanded its order by four boats, bringing Germany’s total to six, while Norway plans to acquire two more, bringing its total to six, which reduces the risk of Canada getting stuck with another orphan sub. This is a significant advantage because, as we’ve learned, maintaining an orphan fleet like Canada’s current Victoria class is exceedingly complex and expensive due to a lack of spare parts and allied participants for collaboration on future upgrades.

On the sensor and combat-systems side, the 212CD moves fully into the digital periscope era. The optronic suite replaces a traditional hull-penetrating periscope with twin non-penetrating masts, HENSOLDT’s OMS-150 and OMS-300, paired with an i360 panoramic system. That combination allows very short exposure times at periscope depth and multispectral imaging, which helps in poor light and clutter, and it integrates directly with the new ORCCA combat system supplied by the KTA Naval Systems joint venture.

ORCCA is the European off-the-shelf brain for 212CD, built to fuse sonar, optronics, ESM, and navigation data and to exchange a common operating picture with allied units. The navigation and mine-avoidance package from Kongsberg, centred on the SA9510S Mk II and EM2040 MIL echo sounders, gives the boat precise bottom-mapping and hazard warning at slow speed. Those elements together explain why 212-series boats have a reputation for being comfortable in tight, shallow, sensor-dense waters that challenge larger hulls.

The propulsion architecture stays true to the 212 family. A PEM fuel-cell air-independent propulsion module supports long, quiet submerged loitering, extending the amount of time the sub can stay submerged without having to snorkel. Public sources do not publish exact submerged endurance figures for the 212CD, but the smaller 212A’s weeks-long AIP benchmarks and the 212CD’s greater internal volume support a reasonable inference that the new design could stay submerged for up to three weeks before having to recharge its batteries. Having said that, it’s important to note that the 212CD is purpose-built to lie in wait at a critical choke point, surprising an adversary with an ambush with little to no warning.

The armament choices reflect that mission focus. The 212CD retains 533 mm torpedo tubes for heavyweight weapons and mine employment. Germany has aligned the class with an updated heavyweight torpedo path and continues to sponsor the IDAS very short-range, tube-launched missile intended as a self-defence option against ASW helicopters and small craft. There is no organic vertical launch system in the design, so any land-attack or long-range anti-ship missile would require a torpedo tube-launched solution and associated integration. For Canada, that means the 212CD is a stealthy ambush submarine first and a strike platform only if Ottawa decides to fund non-trivial integration work.

Source: www.navalnews.com

One tangible edge of the 212CD worth mentioning is its diamond-shaped outer hull. By replacing the usual circular cross-section with flat, sloped sides, the design reflects incoming active-sonar energy away from the emitter, cutting target-echo strength and shrinking detection ranges, similar to how stealth aircraft avoid radar detection and increasingly relevant as ultra-quiet subs blunt passive detection. TKMS and independent reporting note this shaping is explicitly intended to defeat modern mono- and multistatic active sonars, complementing (not replacing) anechoic coatings and other stealth measures.

South Korea’s KSS-III Batch II

This boat comes from a very different design philosophy. Seoul wanted a domestically controlled, blue-water conventional submarine with a meaningful vertical launch battery. Batch I delivered the baseline. In September 2021 the Republic of Korea demonstrated a successful launch of the Hyunmoo-4-4 submarine-launched ballistic missile from the lead boat, which settled any debate about whether the VLS module and ejection sequence work. Batch II expands the architecture to ten VLS cells and incorporates lithium-ion batteries on top of AIP, enhancing submerged endurance and the ability to sustain higher power draws during sprints and evasions. Those are foundational choices if Canada wants a conventional submarine that can do more than lie in wait close to home.

The KSS-III uses a fully digital periscope suite built around non-hull-penetrating optronic masts from Safran, contracted by DSME for the class; Safran’s materials describe these masts as all-electronic sensor heads with multi-channel EO/IR, HDTV imaging, and laser ranging, which aligns with the move away from traditional optical periscopes. Electronic support and communications intelligence are provided by Indra’s Pegaso system, selected for the first Batch II hull and integrated into the submarine’s combat system. The combat management system itself is developed by Hanwha Systems, which serves as the integration backbone for onboard sensors and weapons, including Pegaso. The sonar fit is supplied by LIG Nex1, and Batch II introduces a conformal bow array with more than triple the aperture of the Batch I cylindrical array, along with longer flank arrays, which materially improves both passive sensitivity and active performance.

Size and volume are the other obvious differences. Batch II’s length and displacement figures published by Jane’s and Naval News put the variant at roughly 89 meters and about 3,600 tonnes surfaced, five and a half meters longer than Batch I. The extra volume buys magazine depth, more space for future sensors and unmanned vehicles, and better endurance on station. It also permits a crew and habitability model designed for long patrols. The trade-off is that a larger hull is a little less forgiving in very tight leads or extremely shallow sills.

The weapons architecture is where KSS-III parts company with most Western SSKs. Six 533 mm tubes cover torpedoes, tube-launched anti-ship missiles, and mobile mines, which mirrors European practice. The vertical launch module gives commanders a different playbook. South Korea has proven the cell, and although the ROKN’s SLBM is a national program, the presence of an integrated VLS opens a credible pathway to a conventional land-attack capability via cruise or non-nuclear ballistic missiles. The KSS-III is the first non-nuclear hull in reach that can bring to bear a robust anti-sub, anti-ship, and land attack capability without significant redesign.

For Canadian crews, the KSS-III Batch II’s habitability is a real operational advantage for mixed male and female crews. The larger hull allows for a two-deck layout with separate or configurable berthing, increased privacy, and additional washrooms and showers, which reduces fatigue on long patrols. High automation keeps the core crew around the low-30s, so there is more space per sailor and less friction day to day. Paired with lithium-ion batteries that lengthen quiet endurance between snorts, these features help crews stay rested and effective on longer patrols across three oceans.

The KSS-III Batch II is already in production, with steel already cut and a publicly shown fit that includes a 10-cell VLS and lithium-ion batteries. If Canada signs in 2026, Hanwha says the first boat would arrive around 2032, with four delivered before 2035. The program is domestic today, nine boats for the ROK Navy across three batches, so a Canadian buy would set up the first export sustainment system. That risk is manageable by contract: full technical data and IP access, Canadian-based training pipelines, and a clear division of work between Korean yards and Canadian depots. The remaining concern is fleet commonality, since only two navies would operate the class, but the upside is influence: as the first export customer with up to twelve boats, Canada would hold a strong hand on configuration control and growth options.

What the Two Designs Mean for Canadian Operations

Norway’s and Canada’s “Arctic” are not the same operating problem. Norwegian submarines sail from Haakonsvern near Bergen to the Norwegian and Barents Seas and can be on station quickly. The great-circle distance from Bergen to Tromsø is about 660 nautical miles, and from Tromsø to Longyearbyen on Svalbard, which is Norwegian territory, is roughly 520 nautical miles. Along that coast, warm Atlantic inflow keeps waters largely ice-free year-round, and the Barents Sea has seen pronounced winter ice decline, which shapes patrol patterns around fjords, shelf edges, and chokepoints rather than prolonged under-ice work.

By contrast, Canadian boats leave Halifax or Esquimalt for patrol boxes that are much farther away. Halifax to Iqaluit is about 1,150 nautical miles and Halifax to Resolute Bay nearly 1,980 nautical miles, while an Esquimalt to Beaufort Sea leg to Tuktoyaktuk by sea route is on the order of 3,670 nautical miles. Large parts of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago still retain multi-year ice through summer, which drives different range, endurance, and ice-edge considerations than those built into the German–Norwegian program.

Viewed from Halifax and Esquimalt, the Type 212CD offers a force that makes Canada’s maritime approaches hard for any opponent. The design’s faceted “diamond” outer hull reduces target echo strength under active sonar, complementing very low acoustic signatures and fuel-cell AIP that supports long, quiet waits along shelf breaks and in straits. Its fully digital visuals suite, with twin HENSOLDT optronic masts and the i360 panoramic system, minimizes time and exposure at periscope depth, while the Kongsberg SA9510S Mk II mine-avoidance and bottom-navigation package lowers risk in cluttered, shallow water. These attributes align with a hunter-killer posture in choke points such as the Grand Banks, Cabot Strait, Hecate Strait, and Dixon Entrance, and the KTA “ORCCA” combat system stack is already standardizing across Germany and Norway, which eases NATO integration for Canada.

The drawback emerges when a mission needs organic strike at range. The 212CD is a torpedo-centric SSK, with future tube-launched options possible, but it is not drawn around a vertical launch battery and cannot add one without becoming a different boat. If a patrol box is far from Canada and the task includes land attack or complex multi-axis salvo tactics, that design choice limits options.

The KSS-III flips that calculus for blue-water work. Batch II adds a ten-cell vertical launch module and lithium-ion batteries, which together expand weapon capacity, allow land-attack or anti-ship strikes from covert deep submergence, and improve submerged endurance and sortie pacing. The class is larger than 212CD, with more internal volume and high automation. Hanwha and recent trade press cite a nominal crew in the low 30s, which, combined with the larger hull, improves habitability on 30–60 day trips to distant stations in the Pacific and North Atlantic. These traits are useful when Canada needs a conventional submarine that can hold more weapons, stay longer on station, and influence events at sea and ashore.

Sustainment and schedule are the balancing factors. The 212CD brings an existing European user group and a NATO-standardized combat-system supply chain, which lowers integration friction. KSS-III would require Canada to stand up a bilateral sustainment framework with South Korea, with full data rights and in-country training written into contract from day one, but it buys influence over the export configuration. On schedule, Hanwha publicly states that, if under contract in 2026, it can deliver Canada’s first KSS-III around 2032 and four boats before 2035. This has the added benefit of allowing Canada to dispose of the Victoria class submarines earlier, which could save the Department of National Defence roughly $1 billion.

In short, the German boat brings exceptional stealth shaping, a mature NATO sensor and combat-system ecosystem, and superb choke-point lethality. The Korean boat brings greater weapons volume through VLS, lithium-ion energy for blue-water persistence, more space and automation for crews on long legs, and a vendor-proposed delivery pace that could compress Canada’s transition off Victoria-class.

Recommendation

The KSS-III is the only conventional submarine that can meet all of Canada’s requirements. It combines the blue-water reach and endurance demanded by transoceanic tasking with a vertical launch system that enables credible land-attack and complex anti-surface strike options, supported by lithium-ion batteries that lengthen quiet submerged persistence and improve sortie tempo on distant stations. Its larger hull and higher automation provide the habitability and crew margin needed for 30 to 60 day deployments from Halifax and Esquimalt to the North Atlantic, the Indo-Pacific, and the Arctic ice edge, while remaining within the conventional, non-nuclear profile Canada has set. The design’s modern combat system and sensor suite can be integrated with Canadian and allied command, control, and targeting architectures, and the bilateral sustainment framework required with South Korea can be structured by contract to include full technical data access, in-country training pipelines, and an industrial workshare that anchors through-life support domestically. The delivery cadence proposed for a 2026 award would shorten Canada’s reliance on the Victoria class and reduce associated sustainment exposure during transition, while an initial Canadian order of up to twelve boats would give Ottawa a controlling voice over configuration management, growth paths, and export-variant standards for the life of the class.

Join my newsletter for more analysis on geopolitical, defence, and national security issues and receive a free chapter of my upcoming Canadian military thriller, The Quiet War: Canadian Front.